- Home

- Alrene Hughes

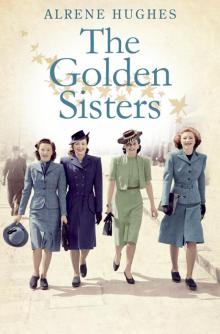

Golden Sisters Page 2

Golden Sisters Read online

Page 2

‘And did you find your sister there?’

Betty shook her head. ‘Jack’s exhausted, he’s having a lie down. I was just reading the paper and it says unclaimed bodies have been moved to St George’s Market. There’s a last chance to identify them before …’ and she began to sob again.

‘Is that where you were going?’

Betty nodded. ‘I was, but I don’t think I can face it. I know I have to go, if she’s there I can’t just leave her, but I’m so scared. I can’t bear to see any more bodies …’

‘Just you sit there while I wash my face and fetch my coat. Then we’ll go and see if we can find your sister.’

St George’s Market was a large red brick Victorian building at the end of May Street in the city centre. It was normally busy with people shopping for fruit and vegetables, meat and fish and household bits and pieces, but today there were no stallholders shouting their wares, no hum of conversations filtering through the wrought iron gates. There was only the sound of weeping and a stench that overpowered the smell of disinfectant.

Betty stopped suddenly. ‘I can’t go in there. I can’t!’ and she turned to walk away.

Martha caught her arm. ‘Yes you can. Think about your sister. You’re doing this for her.’ Martha held out her hand and Betty gripped it tightly. ‘We’ll go in together and find the person in charge.’

Inside, the smell was unbearable. Martha felt in her pocket for a handkerchief and passed it to Betty. ‘Put this over your nose.’

If anything, the sight that met them was worse than the smell – row after row of rough wooden coffins, maybe two hundred or more, many lidded, but some with their lids pushed to one side. A young man in a St John’s Ambulance uniform directed them to the far end of the building where two men sat at a table taking details.

Martha was aware of Betty turning her head from side to side taking in the scene, one moment holding the handkerchief over her nose, the next using it to wipe her eyes. At the table, however, she seemed to regain some composure and gave details of her sister – address, age, physical description. They were assigned a Red Cross nurse who explained she would take them to view the remains along with a young man whose job it was to remove the coffin lids. Martha felt comforted by the calm presence of the nurse, a middle-aged woman like herself. ‘I’ll take you to the ladies who were found near your sister’s house,’ she said.

As the first lid was removed, Betty squeezed Martha’s hand. Together they looked quickly at the body, before turning away to retch at the appalling sight.

‘Is it your sister?’ the nurse asked. Betty shook her head. ‘Let’s move on, then.’

Behind them, a man who was using a watering can to spray disinfectant joined their slow procession. Martha lost count of the number of bodies they saw. Eventually, their nurse suggested they stop for a few minutes and took them to a mobile canteen set up by the Salvation Army.

‘I don’t know how you can do this,’ Martha said to the nurse.

‘Someone has to,’ her smile was kindness itself. ‘But I’ll tell you true, I was a nurse in the last war, served in France so I did, and I never saw sights like this before. There are some girls, and boys too, from the St John’s sent here to help and they don’t last an hour. I shudder to think what memories they’ll carry with them for the rest of their lives.’

‘How long will the bodies be kept here?’ asked Martha.

‘Until Sunday, then they’ll all be buried in a mass grave at the city cemetery,’ she sighed. ‘It’ll be a long weekend.’

‘Is it always nurses who take relatives around?’

‘Mostly, but there are some volunteers, sympathetic people, you know.’ Then with a wry smile she added, ‘With a strong stomach!’ The nurse tilted her head and looked at Martha. ‘Somebody like you could do it.’

Martha shook her head. ‘Oh no, I wouldn’t be able to …’ Her voice trailed off, she could say no more; the thought of the hideous bodies becoming familiar and of trying to console the inconsolable overwhelmed her.

‘I’m sure you could. Why don’t you think about it? We need all the help we can get.’

They sat a while and drank stewed tea from tin mugs and the nurse explained that there were some other bodies that could not be visually identified, though clothes or personal possessions found on the body might still provide a means of identifying them. ‘Will we look for your sister among those people, Betty?’ she asked.

Betty nodded. ‘I’ve come this far and looked at all this. I’m not going to leave until I’m sure she’s not here.’ She turned to Martha, ‘Will you stay with me?’

‘Indeed I will.’

The unidentifiable remains were together in one corner of the market hall. To help with identification, these coffins had chalk markings on the lids listing possessions found on the body and within minutes they had found her. ‘This is her,’ Betty shouted. ‘Apron, knitting, four needles, I know it’s her!’

The lid was pushed back just enough to retrieve the personal effects. The apron and a scrap of knitting on four needles were put into Betty’s hands. ‘Yes, they’re hers – best apron and socks in double rib, always double rib. Never got the hang of four needles myself, but she’d have a pair of socks done in an afternoon.’

‘I’m glad you’ve found her.’ The nurse put her arm around Betty. ‘I’ll write your sister’s name on the lid and give you the coffin number. You’ll be able to contact an undertaker now to arrange the funeral.’

‘Excuse me,’ said Martha, ‘What does it say on this coffin here?’

‘Oh that’s an odd one, so it is. We were discussing it earlier. We think it says “taps stage costume” though what taps have to do with the stage …’

‘Can you open it?’

The nurse pushed the lid to one side to reveal a woman’s legs. Martha bent down and looked at the soles of the shoes. ‘Taps,’ she said. ‘Tap shoes – see the metal tips on the toes and heels? She’s a dancer. What’s she wearing?’

The nurse pushed the lid a little more, revealing a dusty red taffeta skirt and the lower half of a white embroidered gypsy-style blouse. Martha stifled a cry.

‘Do you know who it is?’

‘Yes,’ whispered Martha. ‘It’s Myrtle, my daughter’s friend.’

Chapter 2

Martha took the large soup ladle from the hook at the side of the range and stirred the broth, making sure the pearl barley wasn’t sticking to the bottom. The ham shank she’d used for stock had no meat to speak of on it, but the nourishment in the bone marrow would do them all good. That and the soda bread made from a bottle of soured milk. Waste not, want not.

Sheila was first home and rushed into the kitchen, threw her school bag on the floor and grabbed a glass from the cupboard. ‘I’m dying for a drink.’

‘The water’s off again,’ said Martha, ‘and have you forgotten we’ve only to drink boiled water? There’s a pan full in the back hallway, nice and cool out there.’

‘That’s just one more thing we’ve to thank the Germans for, is it?’

‘Either that or typhoid, take your pick. Did you call at the McCracken’s as you were bid?’

‘Aye they’re fine, but the bombs came close, only a couple of streets away. They’ve been busy cleaning the shop, getting it ready to reopen. I’ve to be there before eight. Saturday’s always busy, but John says it could be heaving tomorrow because people will have run out of food over the last few days with all that’s happened.’

There was the rattle of the gate and Peggy and Pat came round the back of the house, arguing as usual.

‘If Goldstein says there’s going to be no more concerts, there’s nothing we can do about it!’

‘But he formed the Barnstormers to raise money for the war effort and to keep up morale,’ Peggy snapped. ‘That hasn’t changed and, when you think about it, concerts are needed more than ever now.’

‘And what did he say when you told him that?’

‘He said I didn’t

understand. According to him, the military are too busy for concerts and everybody else just wants to hide under the stairs or up the mountain.’

‘Well, there you are then!’

‘You’re home earlier than I expected,’ said Martha, ‘and in good humour I see.’

‘There were buses running up the Oldpark Road,’ said Pat. ‘Packed, mind you, but we all squeezed on. What’s for tea?’

‘Broth.’

‘Tell me you haven’t put any of that barley in it,’ said Peggy.

‘It’ll fill you up more.’

‘No it won’t.’

‘Yes it will,’ argued Martha.

‘No it won’t, because I’m not eating it!’

‘Where’s Irene?’ asked Pat, changing the subject. ‘She’s coming home tonight, isn’t she?’

‘As far as I know, she and Sandy were leaving the hotel in Bangor early this morning and he was dropping her off at the factory before reporting for duty at his base.’

‘She’ll be really sad saying goodbye to Sandy, won’t she?’ said Sheila.

‘I’d have thought that was obvious, seeing as they’ve only been married two days!’ snapped Peggy.

‘Not necessarily, she might be happy because she’s back home with us.’

‘What, back to no water, air raids every night and broth for tea!’

‘Will you two stop bickering and let’s have a quiet meal for a change,’ said Martha as she served up the broth, pearl barley and all. They ate in silence for a while then Martha asked, ‘What’s the news from Stormont today, Pat?’

‘You’ll never believe it, but they’re going to paint the building with pitch and cow dung!’

‘What?’

‘Aye, that beautiful white building.’

‘Why would they do that?’

‘Because it gleams in the moonlight and the Germans can use it to pinpoint anything they want to bomb.’

‘It’s a bit late now, isn’t it?’ laughed Peggy.

Pat gave her a withering look. ‘They’re doing it for the next time they come. The ministry’s making plans to keep people safe.’

‘Like I said, it’s a bit late now!’

Pat ignored her and turned to Martha. ‘We’re going to try another evacuation programme – Sheila could get on it. I could put her name down if you like?’

‘I don’t know, Pat. Maybe she’s better here with us than with strangers in the back of beyond.’

‘Ach, Mammy, you’re the one listens to the wireless: the Luftwaffe will be back any day now.’ Pat was into her stride. ‘We’ll coordinate the evacuation at the ministry, the transport will be laid on and inspections made of those willing to take the children.’

There was a clatter of cutlery at the end of the table and Sheila was on her feet. ‘I’m not a child, I’m fourteen and no one is going to tell me I have to leave my home! It’s like we’re giving into the Nazis. You’re all going to stay here and so am I!’

Pat was about to answer, but Martha stopped her. ‘Hold on a wee minute, Sheila, this isn’t like it was before. Now there are bombs falling on us and there are hundreds being buried as we speak. Next week it could be thousands.’

‘But, Mammy–’

‘No, Sheila, this is something I’m going to have to think seriously about.’

They were just clearing the table when Irene came in. Martha could see she’d been crying, but the others didn’t seem to notice as they plied her with questions about her trip to Bangor. Soon, she was telling them all about it.

‘The weather was lovely and so was the hotel. We went swimming in Pickie Pool and dancing at Caproni’s. They had a really good resident band with two girls singing all the latest songs. Some of them would be good for us to learn, if you could get the sheet music, Peggy.’

‘You make a list of the titles and I’ll see if we’ve got them in the shop.’

Martha disappeared into the kitchen and returned with Irene’s tea on a tray. ‘Now give her a chance to eat, will you?’

Peggy waited until Martha was back in the kitchen then said, ‘You know, if Goldstein can’t organise concerts, maybe we could sing in a dance hall.’

‘No we couldn’t. Those people are professional singers,’ argued Pat. ‘We’re just amateurs.’

Peggy was affronted. ‘Amateurs! We’re not amateurs.’ She turned to Irene and demanded, ‘How good were those girls in Caproni’s? They weren’t better than us, were they?’

Irene paused, a piece of soda halfway to her mouth, and considered. ‘They had style, you know, hair, make-up, beautiful dresses. They seemed to move very well; a bit like you’d see in a film.’

‘Yes, yes,’ Peggy interrupted, ‘but what about the singing, the harmonies, the sound?’

‘Well …’ Irene returned the soda to the tray. Her sisters leaned forward in their seats.

‘Well, were they or weren’t they?’ shouted Peggy.

‘What?’

‘Better singers than us?’

Irene laughed, ‘No, they weren’t a patch on us!’

The whoops and cheers brought Martha from the kitchen. ‘Bless us all!’ she said. ‘What on earth are you about now?’

‘Nothing,’ said Peggy calmly, ‘we’re just very happy Irene’s home.’

Later, as they sat in the front room with the blackout curtains drawn, Martha told them of her visit to the market with Betty and her belief that Myrtle was there.

‘Right enough,’ said Peggy, ‘the Templemore Tappers were dressed in gypsy blouse costumes for their final dance routine and we all left the concert without changing because of the air-raid warning. So, unless there’s another member of the Tappers missing, it probably is Myrtle.’

‘God love her,’ Pat was close to tears. ‘We can’t leave her there. We need to tell her family.’

Irene, who had listened to the news about Myrtle with her head bowed, spoke softly, ‘I’ll talk to Robert McVey at work; he’s in touch with her family. What do they need to do?’

‘They should go to the market tomorrow and ask to see the unidentifiable bodies–’

‘Unidentifiable? What does that mean?’ The panic rose in Irene’s voice.

Martha realised her mistake. ‘No, no it’s all right, it’s all right.’

But Irene was on her feet. ‘I’ll go there now! Sure, I’ll know if it’s her.’

Martha caught her arm before she reached the door. ‘You mustn’t go! You don’t need to.’

‘Yes I do. I can tell them it’s her.’

‘There’s no need. Just make sure her family come to the market tomorrow and I’ll be there waiting for them. Tell them I’ll stay with them until they’re sure they’ve found Myrtle.’

Irene looked puzzled. ‘Mammy, why would you be at the market?’

‘Because … because I’ve volunteered to help them with the relatives.’

‘Why would you do that?’

It was a question Martha had been asking herself all afternoon and she struggled to explain. ‘I was asked and I couldn’t say no. Somebody has to …’ Now, looking at Irene’s tear-stained face, Martha knew she’d made the right decision.

‘Irene, why don’t you go to bed now? You’re exhausted, love. I’ll be with Myrtle tomorrow until her family comes, so don’t you worry. Maybe we should all go up and get a bit of sleep, for there’ll surely be another air-raid warning tonight and when it happens I want all of you down here under the stairs and that includes you, Peggy – no staying in your bed like you usually do.’

Pat couldn’t sleep. There had been no opportunity to talk to her mother about the plan to spend the night on the Cave Hill and maybe that was as well, because she couldn’t trust herself to explain it without being embarrassed. She could always wait until tomorrow night then simply announce where she was going, but what if her sisters were there? The last thing she wanted was to be teased about being out at night with William.

She waited until she was sure Irene was asleep then slipped out o

f bed. The light was still on in the front bedroom. She knocked and went in. Martha was sitting up in bed, totting up the week’s expenditure in her housekeeping book.

‘Mammy, can I ask you something?’

‘There’s no harm in asking,’ said Martha, but something in Pat’s tone put her on her guard.

‘There’s a team from the ministry going to talk to the people spending their nights up the Cave Hill and they want me to be a part of it.’

‘Is that so?’ Martha waited for the rest.

‘They’re going up there tomorrow night and I wanted to ask you if I could go?’

‘And who exactly are “they”?’

‘There’ll be six of us – three men and three women.’

Martha raised an eyebrow. ‘Oh aye, and is William Kennedy one of the men?’

Pat felt the blush burn her face and bent her head. ‘He is, Mammy.’

The seconds ticked by, Pat looked up. Her mother was staring straight ahead. Eventually she spoke. ‘I don’t like it, Pat. William Kennedy is a good man, but even good men …’

Pat blushed again.

God help me, thought Martha. It was easy when they were wee girls and she knew where the boundaries were. Was she being unreasonable, unfair?

‘You like William, don’t you?’

Pat nodded and bit her lip.

‘Has he said anything about how he feels?’ Pat didn’t answer. ‘I’ll take that as a “no” then. Look, Pat, I don’t want you hurt.’ Martha struggled to find the right words to express her fears. ‘You mustn’t do anything foolish, but you know that, don’t you?’

‘It’s important I do this so the ministry can find out why people go up there. You’re going to the market to help – it’s the same thing.’

Martha sighed. ‘You see there on the dressing table … the big hatpin? Get that and put it in your lapel when you go tomorrow night and remember to keep your wits about you.’

The Girl from the Corner Shop

The Girl from the Corner Shop Martha's Girls

Martha's Girls A Song in my Heart

A Song in my Heart Golden Sisters

Golden Sisters